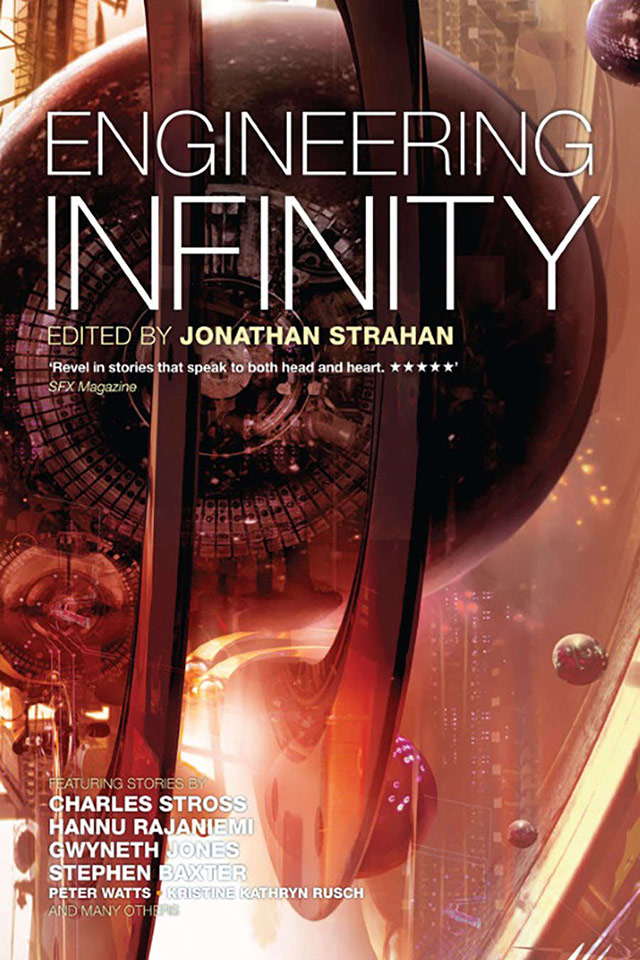

Cover illustration by Stephan Martiniere.

A Soldier of the City

In Engineering Infinity, edited by Jonathan Strahan. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010. ISBN 978-1907519529. Reprinted in The Year’s Best Science Fiction: Twenty-Ninth Annual Collection, edited by Gardner Dozois. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2012. ISBN 978-1250009784. Reprinted in War and Space: Recent Combat, edited by Rich Horton and Sean Wallace. Gaithersburg: Prime, 2012. ISBN 978-1607013372. Reprinted online in Clarkesworld Issue 123 (December 2016).For uncounted millennia the cities of Babylon — warlike Ashur, wealthy Babylon-Borsippa, peaceful Isin, and all the rest — have spun in the light of the Old Galaxy, revolving about the great black hole called Tiamat, sustained by its power and protected by the gods, while on the worlds of the surrounding stars the nomads, less fortunate, shiver in the dark.

But now the nomads have built a weapon that can kill a god.

The gods are mortal.

Gula, the Lady of Isin, is dead.

And Ishmenininsina Ninnadiïnshumi, soldier of the city of Isin, has lost the one woman he’s ever loved.

In the moment of the blast, Ish was looking down the slope, toward the canal, the live feed from the temple steps and the climax of the parade. As he watched, the goddess suddenly froze; her ageless face lost its benevolent smile, and her dark eyes widened in surprise and perhaps in fear, as they looked—Ish later would always remember—directly at him. Her lips parted as if she was about to tell Ish something.

And then the whole eastern rise went brighter than the Lady’s House at noonday. There was a sound, a rolling, bone-deep rumble like thunder, and afterwards Ish would think there was something wrong with this, that something so momentous should sound so prosaic, but at the time all he could think was how loud it was, how it went on and on, louder than thunder, than artillery, than rockets, louder and longer than anything Ish had ever heard. The ground shook. The projection faded, flickered and went out, and a hot wind whipped over the hilltop, tearing the net from its posts, knocking Mâra to the ground and sending her football flying, lost forever, out over the rooftops to the west.

From the temple district, ten leagues away, a bright point was rising, arcing up toward the dazzling eye of the Lady’s House, and some trained part of Ish’s mind saw the straight line, the curvature an artifact of the city’s rotating reference frame; but as Mâra started to cry, and Ish’s wife Tara and all his in-laws boiled up from around the grill and the picnic couches, yelling, and a pillar of brown smoke, red-lit from below, its top swelling obscenely, began to grow over the temple, the temple of the goddess Ish was sworn as a soldier of the city to protect, Ish was not thinking of geometry or the physics of the coriolis force. What Ish was thinking—what Ish knew, with a sick certainty—was that the most important moment of his life had just come and gone, and he had missed it.